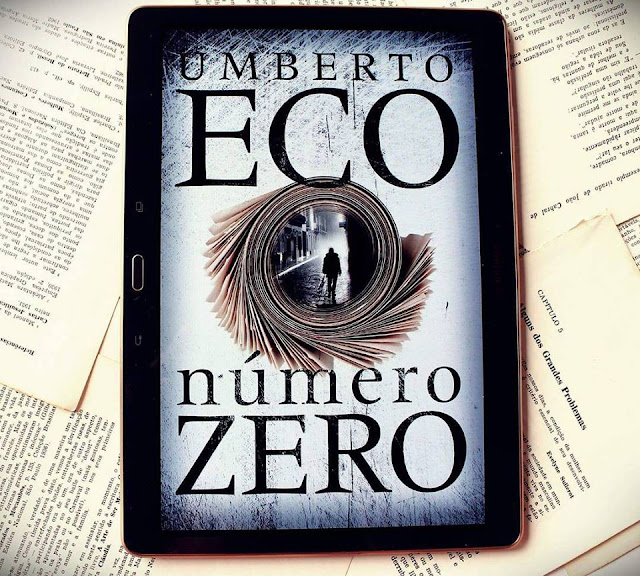

The venture is financed by Commendator Vimercate, who owns a television channel, a dozen magazines, and a chain of hotels and rest homes. He dropped out of university, gave up translating and turned to journalism, proof-reading and ghost-writing, moving from city to city, wherever he could find work.Ħ He is hired by Simei to work on Domani (Tomorrow), a newspaper that will never be published. But he soon grew tired of the baroque ways of the Italian academic system, and equally tired of rendering three-volume works on the Zollverein, the German customs system, in dolce stil novo. His South Tyrolean grandmother had made him speak German as a child, and from his first year of university he took to translating books to pay for his studies. Amusingly (from my point of view, at least) he had begun his career as a translator. The narrator, Colonna, is a hack journalist, now in his fifties, and a loser. But in Eco’s novel there were going to be twelve issues-twelve dummy issues of a newspaper that would never be published.ĥ The action takes place over three months in 1992. It was the same table where we’d discussed The Prague Cemetery on our first encounter four years before.Ĥ A numero zero is the dummy issue of a new publication, the trial issue, put together to see how it might look. We sat at a table under the line of cypress trees in his garden as he described the new novel. Work on the novel was almost complete and Eco’s main concern seemed to be the title.ģ “How do you say numero zero in English?” he asked. Mario Andreose and Drenka Willen, his Italian and American editors, were there for a few days in summer 2014, and I was invited across one afternoon.

As always I could rely on Eco’s amiability and enthusiasm in the translation process, though we met to discuss the book only twice-first, before the Italian edition had been published, and then, after I had completed the translation, to resolve outstanding problems before I submitted the finished manuscript to the publishers.Ģ The first of these meetings took place at Eco’s summer home in the Apennines, just over an hour’s drive from where I live.

1 The Prague Cemetery was published by Harvill Secker (London) and Houghton Mifflin (New York) in 201 (.)ġ This was my third book-length translation of a work by Umberto Eco 1 and, though shorter than the previous two, my task was more complex for reasons I hope to illustrate.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)